New Pet Food Labeling Standards: What's New? Specialized News Column for Environmentalists and Environmentally Concerned Citizens On April 30, 2025, the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (MOFA) issued a notice of partial amendment to the ‘Standards and Specifications of Feed, etc.’, establishing separate labeling standards for pet food (dog and cat). This is an important change for consumers' right to know and fair competition in the industry, as the legal distinction between pet food and livestock food is not clear. The revision strengthens the responsibility of manufacturers and salespeople to prove each statement on the packaging of pet food. In particular, it requires the type of food (complete food/other food) to be labeled, the content to be labeled when emphasizing specific ingredients and functions, the product name to be strengthened, the responsibility of specialized retail salespeople to be expanded, and the labeling conditions to be subdivided into ‘...

Beekeepers across the U.S. see unprecedented honeybee die-offs

Beekeepers across the U.S. see unprecedented hBeekeepers around the U.S. have seen many of their bees die of an unknown cause over the winter this year. New York’s largest apiary was spared, but others weren’t so lucky.

“Based on early numbers that are coming in, it’s suggestive that this will be the biggest loss of honeybee colonies in U.S. history,” said Scott McArt, director of the Dyce Lab for Honeybee Studies at Cornell University.

Between June 2024 and March 2025, commercial beekeepers have had an average loss of 62% of their hives, according to a survey conducted by Project Apis m., a nonprofit that supports beekeepers.

Moroch tends to the hives at Kutik's Everything Bees. (Emily Kenny/Spectrum News 1)

“We estimate that we’ve lost 1.6 million hives, and that’s only an estimate. The U.S. has 2.7 million, so that’s a really high proportion of the colonies in the U.S. that are gone,” said Danielle Downey, executive director of Project Apis m.

The economic impact of is estimated to be more than $600 million because of losses in honey production, pollination income and the costs to replace the colonies. The cause of this large die-off of bees is still unknown, but the industry is looking for answers, Downey said.

“Cornell is doing the analysis of the pesticide residues; we hope to have those results in the next month or two, and that will be great information if there’s a cause,” she said. “The pathology study, that’s looking at the viruses and the gut parasites.”

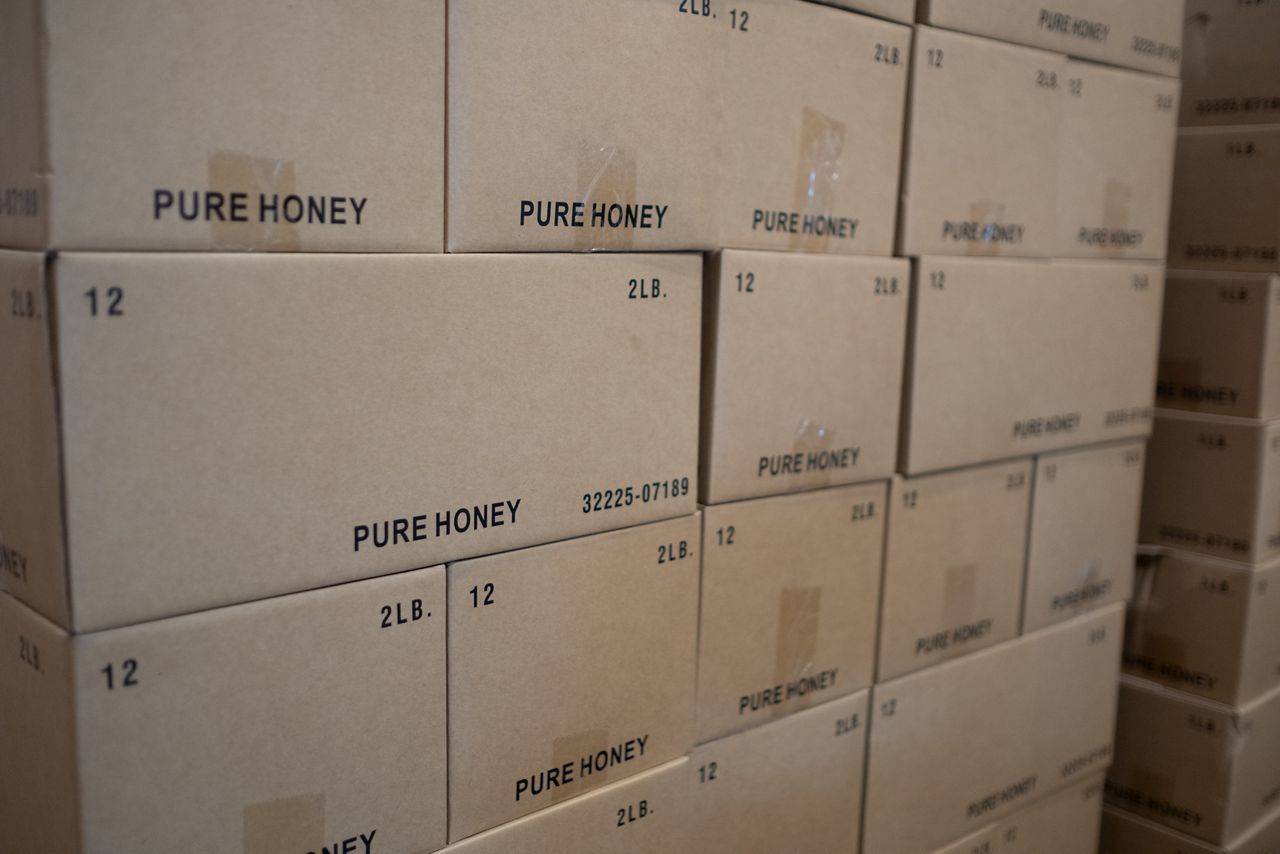

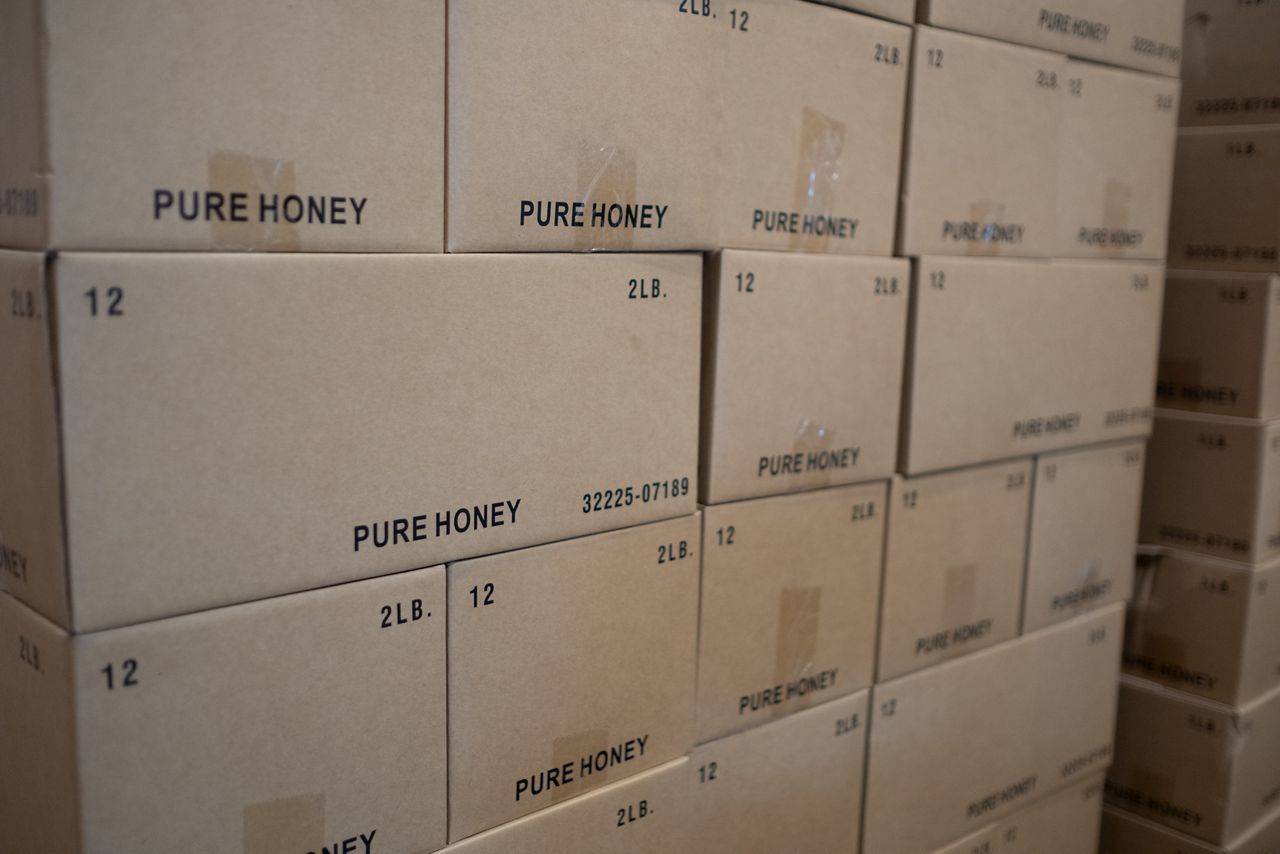

Honey from Kutik's Everything Bees. (Emily Kenny/Spectrum News 1)

The Dyce Lab for Honeybee Studies will also look at varroa mites, a common parasite that impacts bees, environmental factors, management factors and chemical exposures.

About 20 years ago, there was a die-off of bees that researchers were never able to solve. They called it Colony Collapse Disorder, Downey said.

“It looked like a flourishing hive. You could tell because it had lots of brood, bees and food, and there was no obvious pathology that would have killed it, but suddenly the adult bees are gone,” Downey said. “You have a queen, and a few younger worker bees that are attending to her and lots of brood and food, so there was evidence of that whole metropolis, but nobody’s home.”

Moroch marks a queen with a blue dot. Kutik's are one of the only queen rearing services in the Northeast. (Emily Kenny/Spectrum News 1)

Honeybees are not native to North America, but due to the nature of large-scale agriculture, they are used as pollinators for many crops such as almonds, apples, cherries, melons, blueberries and pumpkins.

“The way that we grow food in large, consolidated monocrops, there’s no natural pollinator that could potentially even do that job. To have these natural pollinators, you have to provide a habitat and take care of it and so much of our agriculture is not a natural system anymore. We really rely on these honeybees, and if they fail, we don’t have a backup plan,” Downey said.

It is normal for beekeepers to lose between 30% and 40% of their bees through the winter, but more than 60% is unprecedented.

A sign hangs in Kutik's Everything Bees. (Emily Kenny/Spectrum News 1)

“These colonies are weak. They may not even have enough to split,” Downey said.

Lindsey Moroch, an owner of Kutik’s Everything Bees in Oxford, said they were lucky to not see the same number of die-offs as other beekeepers, but they did scale back their pollination services this year.

“This year, it was so cold in the Carolinas that we didn’t see a ton of growth. We expect our colonies to brood up or to grow at a certain rate there and because it was so cold, they weren’t doing that,” Moroch said.

Due to this, they didn’t send as many bees to California in January to pollinate the almond trees, which are the first contract of the year for many migratory beekeepers who offer pollination services. It was around this time that Moroch started hearing more about these die-offs.

“We had growers saying 'we’ll take what you can give us. We know you’re going to have healthy bees and if you can provide us with something at a decent grade, we will take it,' so we went at that point, but certainly not to the scale that we normally do,” Moroch said.

Moroch said the smoke is meant to help mask a pheromone that bees release when they fear an intruder in the hive. (Emily Kenny/Spectrum News 1)

At the height of the season, they have about 9,000 hives they use for pollination contracts from California almonds to North Carolina blueberries and back home for New York’s apple season.

“Another thing that has made this season so noteworthy is in New York state, the highest loss rate was 50% [this year]. Last year was 18%, some of the lowest rates ever so you go from a season like that with some of the lowest losses ever on record to cataclysmic, people losing everything they’ve got,” Moroch said.

Most farmers have some form of crop insurance that protects them from catastrophic losses because of uncontrollable factors like weather, but insurance for bees can be a challenge.

Honey production is a large portion of the business they do at Kutik's Everything Bees. (Emily Kenny/Spectrum News 1)

“As far as losses go, if you say, ‘oh, my bees died’ and there's nothing you can pinpoint, they wonder [if it is] just your carelessness? There are so many factors if it’s not tangible in some way,” Moroch said.

In an effort to protect the bees that survived the winter, Moroch said taking precautions when using pesticides is critical.

“Being conscious if you’re planning on spraying something or you want to use some sort of pest control, do not do it while things are in bloom because that’s when pollinators are coming to it, so don’t put them through that exposure,” she said. “Support your local beekeepers; we’re doing the best that we can.”oneybee die-offs

Beekeepers across the U.S. see unprecedented hBeekeepers around the U.S. have seen many of their bees die of an unknown cause over the winter this year. New York’s largest apiary was spared, but others weren’t so lucky.

“Based on early numbers that are coming in, it’s suggestive that this will be the biggest loss of honeybee colonies in U.S. history,” said Scott McArt, director of the Dyce Lab for Honeybee Studies at Cornell University.

Between June 2024 and March 2025, commercial beekeepers have had an average loss of 62% of their hives, according to a survey conducted by Project Apis m., a nonprofit that supports beekeepers.

Moroch tends to the hives at Kutik's Everything Bees. (Emily Kenny/Spectrum News 1)

“We estimate that we’ve lost 1.6 million hives, and that’s only an estimate. The U.S. has 2.7 million, so that’s a really high proportion of the colonies in the U.S. that are gone,” said Danielle Downey, executive director of Project Apis m.

The economic impact of is estimated to be more than $600 million because of losses in honey production, pollination income and the costs to replace the colonies. The cause of this large die-off of bees is still unknown, but the industry is looking for answers, Downey said.

“Cornell is doing the analysis of the pesticide residues; we hope to have those results in the next month or two, and that will be great information if there’s a cause,” she said. “The pathology study, that’s looking at the viruses and the gut parasites.”

Honey from Kutik's Everything Bees. (Emily Kenny/Spectrum News 1)

The Dyce Lab for Honeybee Studies will also look at varroa mites, a common parasite that impacts bees, environmental factors, management factors and chemical exposures.

About 20 years ago, there was a die-off of bees that researchers were never able to solve. They called it Colony Collapse Disorder, Downey said.

“It looked like a flourishing hive. You could tell because it had lots of brood, bees and food, and there was no obvious pathology that would have killed it, but suddenly the adult bees are gone,” Downey said. “You have a queen, and a few younger worker bees that are attending to her and lots of brood and food, so there was evidence of that whole metropolis, but nobody’s home.”

Moroch marks a queen with a blue dot. Kutik's are one of the only queen rearing services in the Northeast. (Emily Kenny/Spectrum News 1)

Honeybees are not native to North America, but due to the nature of large-scale agriculture, they are used as pollinators for many crops such as almonds, apples, cherries, melons, blueberries and pumpkins.

“The way that we grow food in large, consolidated monocrops, there’s no natural pollinator that could potentially even do that job. To have these natural pollinators, you have to provide a habitat and take care of it and so much of our agriculture is not a natural system anymore. We really rely on these honeybees, and if they fail, we don’t have a backup plan,” Downey said.

It is normal for beekeepers to lose between 30% and 40% of their bees through the winter, but more than 60% is unprecedented.

A sign hangs in Kutik's Everything Bees. (Emily Kenny/Spectrum News 1)

“These colonies are weak. They may not even have enough to split,” Downey said.

Lindsey Moroch, an owner of Kutik’s Everything Bees in Oxford, said they were lucky to not see the same number of die-offs as other beekeepers, but they did scale back their pollination services this year.

“This year, it was so cold in the Carolinas that we didn’t see a ton of growth. We expect our colonies to brood up or to grow at a certain rate there and because it was so cold, they weren’t doing that,” Moroch said.

Due to this, they didn’t send as many bees to California in January to pollinate the almond trees, which are the first contract of the year for many migratory beekeepers who offer pollination services. It was around this time that Moroch started hearing more about these die-offs.

“We had growers saying 'we’ll take what you can give us. We know you’re going to have healthy bees and if you can provide us with something at a decent grade, we will take it,' so we went at that point, but certainly not to the scale that we normally do,” Moroch said.

Moroch said the smoke is meant to help mask a pheromone that bees release when they fear an intruder in the hive. (Emily Kenny/Spectrum News 1)

At the height of the season, they have about 9,000 hives they use for pollination contracts from California almonds to North Carolina blueberries and back home for New York’s apple season.

“Another thing that has made this season so noteworthy is in New York state, the highest loss rate was 50% [this year]. Last year was 18%, some of the lowest rates ever so you go from a season like that with some of the lowest losses ever on record to cataclysmic, people losing everything they’ve got,” Moroch said.

Most farmers have some form of crop insurance that protects them from catastrophic losses because of uncontrollable factors like weather, but insurance for bees can be a challenge.

Honey production is a large portion of the business they do at Kutik's Everything Bees. (Emily Kenny/Spectrum News 1)

“As far as losses go, if you say, ‘oh, my bees died’ and there's nothing you can pinpoint, they wonder [if it is] just your carelessness? There are so many factors if it’s not tangible in some way,” Moroch said.

In an effort to protect the bees that survived the winter, Moroch said taking precautions when using pesticides is critical.

“Being conscious if you’re planning on spraying something or you want to use some sort of pest control, do not do it while things are in bloom because that’s when pollinators are coming to it, so don’t put them through that exposure,” she said. “Support your local beekeepers; we’re doing the best that we can.”oneybee die-offs

댓글

댓글 쓰기