Unstung Heroes: Canada’s Honey Bees Aren’t Disappearing – They’re Thriving

Unstung Heroes: Canada’s Honey Bees Aren’t Disappearing – They’re Thriving

Fifty years ago, everyone was abuzz about bees. And not in a good way. Giant swarms of aggressive Africanized honey bees had escaped from a research facility in Brazil in 1957 and by the mid-1970s were making their way slowly northward through Mexico, having killed an estimated 1.000 people along the way. With these “killer bees” then on the doorstep of Texas, all of North America came to see bees as a dire threat to public safety.

Popular culture quickly latched onto the killer-bee phenomenon. Among the results was a famous 1975 Saturday Night Live skit with the deadly insects portrayed by John Belushi, Dan Ackroyd and Elliott Gould as sneering, home-invading Mexican bandits, as well as a requisite star-heavy Irwin Allen disaster movie – 1978’s The Swarm.

The killer-bee scare eventually fizzled out in the early 1990s when the deserts of the American Southwest put an end to their northward trek. Yet public panic about bees never really went away. It just turned full circle. Today, it’s no longer swarms of killer bees that pose an existential threat to humanity. Rather, it’s that the bees themselves are dying at an alarming rate…which poses an existential threat to humanity.

Colony Collapse Disorder

The shift in public sentiment from bees as killers to victims began in 2007. That was the year colony collapse disorder (CCD) – the unexplained, large-scale disappearance of honey bees – was first reported in the U.S. While a yearly loss of 15 percent of an apiary’s colonies was then considered typical among beekeepers, CCD was marked by annual losses of 50 percent or more. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, CCD was “inconsistent with any known causes of honey bee death” and was recognizable by the “sudden loss of a colony’s worker bee population with very few dead bees found near the colony.” The bees appeared to leave the hive and never come back.

Killer buzz: Throughout the mid-1970s, popular culture leaned hard on the killer bee threat, including a famous Saturday Night Live skit (top) featuring, left to right, Elliott Gould, Dan Ackroyd, John Belushi, Gilda Radner and Chevy Chase, and the 1978 disaster movie The Swarm with, at bottom, Olivia de Havilland about to meet her demise. (Sources of screenshots: (top) YouTube/Saturday Night Live; (bottom) Horror Ghouls)

Killer buzz: Throughout the mid-1970s, popular culture leaned hard on the killer bee threat, including a famous Saturday Night Live skit (top) featuring, left to right, Elliott Gould, Dan Ackroyd, John Belushi, Gilda Radner and Chevy Chase, and the 1978 disaster movie The Swarm with, at bottom, Olivia de Havilland about to meet her demise. (Sources of screenshots: (top) YouTube/Saturday Night Live; (bottom) Horror Ghouls)The following year, the Canadian Association of Professional Apiculturists (CAPA) released its own initial study on the CCD phenomenon, charting an unprecedented 35 percent colony loss rate. “Successive annual losses at [these] levels…are unsustainable by Canadian beekeepers and are likely to lead to decreased honey production and shortages of colonies available for pollination,” the report warned. Every year since 2008 the CAPA has reported on the winter fatality rate for honey bee colonies, revealing seasonal losses as high as 45 percent. The annual loss average is now pegged at 28 percent, or nearly double the pre-2007 figure.

From killers to victims: Since “colony collapse disorder” was first identified in North America in 2007, media outlets have repeatedly predicted the imminent demise of honey bees.

From killers to victims: Since “colony collapse disorder” was first identified in North America in 2007, media outlets have repeatedly predicted the imminent demise of honey bees.Such worrisome statistics gave rise to a steady stream of apocalyptic headlines predicting the imminent annihilation of honey bees across North America. Articles include “Last flight of the honeybee?” from The Guardian in 2008, “Huge Honey Bee Losses Across Canada” in CBC in 2013, and “Canada’s bee colonies see worst loss in 20 years” in CBC three years ago. As each story dutifully warns readers, given bees’ crucial role in pollinating crops including canola, soybeans, apples, tomatoes, berries and so on, their disappearance spells chaos for our food supply – and could lead to widespread human hunger.

This year is no exception. Following a report from Washington State University entomologists that predicts a 2025 die-off rate of up to 70 percent for American honey bee colonies, the Cassandras swung swiftly back into action. “Scientists warn of severe honeybee losses in 2025” screams an article on the NBC News website. “Bees Give Us Food, Pollination and Natural Medicines – and They’re Disappearing” intones the Epoch Times. “The Bees are Disappearing Again” says the New York Times, with this last example at least hinting at the regularity of the occurrence.

If it’s spring in North America, the bees must be disappearing. Again.

Many Bee Foes

“It is alarming,” says entomologist Ernesto Guzman of the new U.S. projections. Guzman is director of the University of Guelph’s Honey Bee Research Centre and president of CAPA. He notes that while Canada has not yet seen evidence of a potential 70 percent decline, last year Ontario suffered a 50 percent loss rate and PEI lost 61 percent of its colonies. “Beekeepers who lose such a high rate of colonies can be out of business pretty quickly,” Guzman warns.

In 2013, the European Union banned three of the most popular neonics out of caution rather than direct evidence the pesticides were killing bees. In Canada the issue was studied intensely by the federal Pest Management Regulatory Agency, which ultimately determined neonics provide key benefits to the agricultural sector and, when applied properly, do not pose a significant threat to bee health.

As Guzman explains in an interview, while the U.S. narrowly defines CCD as the mysterious and unexplained disappearance of bees, in Canada colony collapse refers more broadly to any mass bee death. And there’s a long list of causes to consider. “The main factor in winter deaths is varroa mites,” Guzman says. The varroa mite is a tiny parasite originally from Asia that feeds on a honey bee’s fat cells. It was first identified in North America in 1987 and has since become the number one danger to bee health. Among other major health threats, Guzman cites viruses carried by the mites, as well as certain pesticides.

In the early-2010s, a new class of pesticide called neonicotinoids (or neonics) earned widespread notoriety for its alleged role in CCD. This led to numerous calls from environmentalists to ban the pesticide, which is applied directly to seeds and is thus far more efficient than spraying entire fields. In 2013, the European Union banned three of the most popular neonics out of caution rather than direct evidence the pesticides were killing bees. In Canada the issue was studied intensely by the federal Pest Management Regulatory Agency, which ultimately determined that neonics provide key benefits to the agricultural sector and, when applied properly, do not pose a significant threat to bee health.

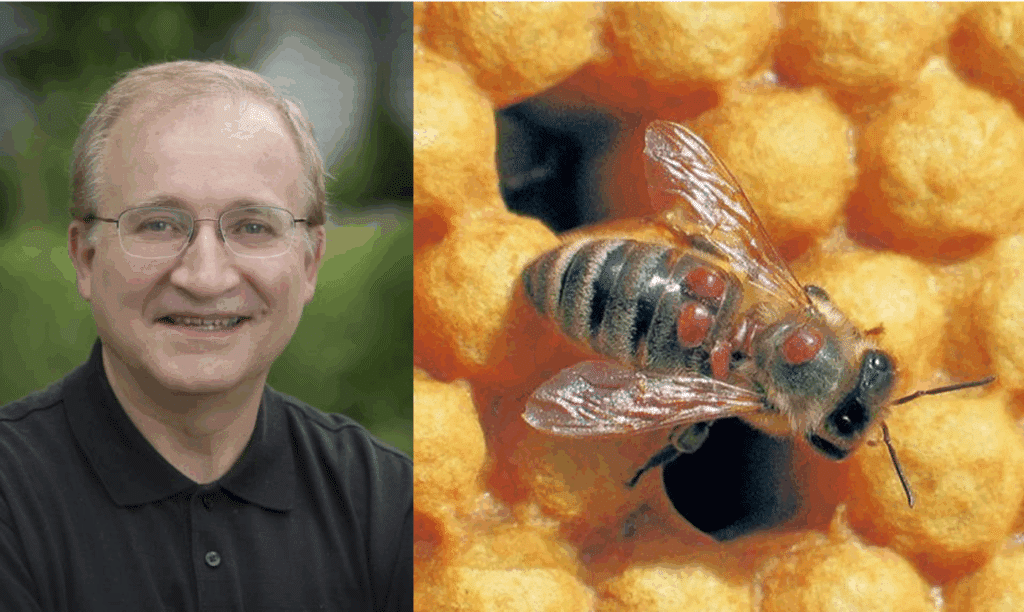

According to Ernesto Guzman, director of the University of Guelph’s Honey Bee Research Centre, honey bees in Canada face a long list of threats, especially from the varroa mite. Shown at right, a bee suffering from a varroa mite infestation. (Source of left photo: University of Guelph)

According to Ernesto Guzman, director of the University of Guelph’s Honey Bee Research Centre, honey bees in Canada face a long list of threats, especially from the varroa mite. Shown at right, a bee suffering from a varroa mite infestation. (Source of left photo: University of Guelph)Additional risks to bees include winter weather, poor diet and the stress of transportation, since many bee colonies are trucked long distances to pollinate crops in different regions. On the Prairies, many beekeepers bring their bees inside for the winter while in Eastern Canada hives are typically wrapped in insulation – moisture inside a hive at this time can be deadly for the bees. Even treating certain bee problems can do as much harm as good. Guzman notes research by a colleague at the University of Guelph that revealed a common miticide used to combat the varroa mite was also toxic to bees and caused them to forget how to fly home. “When I talk about pesticides, it is not just neonics,” adds Guzman; it also includes medical treatments. A fulsome explanation for the post-2007 spike in bee fatalities, he says, involves “not on a single factor, but a number of factors.”

Whole Lotta Buzz

At the heart of all this calamitous data, however, lies a large, hairy, black-and-yellow striped conundrum. How is it possible for a species to be in an apparent continuous and catastrophic state of decline for nearly two decades, but never actually fall in number? For despite the constant supply of grave predictions, Canada’s beehives are actually buzzing with life.

In 2007, according to Statistics Canada, there were 589,000 honey bee colonies in Canada. Last year Statcan counted 829,000 colonies – just shy of 2021’s all-time high of 834,000. Considering a conservative summertime average of 50,000 bees per colony, this suggests there are approximately 12 billion more honey bees in Canada today than when the Bee Apocalypse was first announced.

As for Canadian beekeepers, their numbers have also been growing steadily and now stand at 15,430 – the most recorded since 1988, back when killer bees were still a thing. (There were an astounding 43,340 beekeepers in 1945, when many Canadians were raising their own bees due to wartime sugar rationing, as well as to supply beeswax for ammunition belts.) As CAPA’s 2024 report acknowledges, “The Canadian beekeeping industry has been resilient and able to grow, as proven by the overall increase in the number of bee colonies since 2007 despite the difficulties faced every winter.”

Despite annual winter colony losses averaging 28 percent since 2007, the number of honey bee colonies in Canada has grown robustly over this time. (Source of data: Canadian Association of Professional Apiculturists and Statistics Canada; chart by C2C Journal)

Despite annual winter colony losses averaging 28 percent since 2007, the number of honey bee colonies in Canada has grown robustly over this time. (Source of data: Canadian Association of Professional Apiculturists and Statistics Canada; chart by C2C Journal)The same holds true in the U.S., where CCD was first identified. In the face of a near-constant barrage of bee doom, earlier this year the Washington Post seemed to surprise itself when it reported that, “America’s honeybee population has rocketed to an all-time high.” Over the past five years, the Post found the U.S. has added 1 million new bee colonies – or around 50 billion more bees. In fact, since the initial report of CCD in 2007, honey bees have become that country’s fastest-growing type of livestock, according to the U.S. agricultural census.

But how is this possible? The standard bee narrative is one of constant and precipitous decline, whereas bee statistics reveal the exact opposite. The answer to this puzzle lies in the nature of the bee economy. As is usually the case when there’s a need to be filled, the market has the answer.

Are honey bees disappearing?

Show Me the Honey

Todd Kalisz is CEO and master beekeeper of Dancing Bee Equipment based in Port Hope, Ontario and is deeply involved in all aspects of the industry. With branch operations in Manitoba and Indiana, his firm runs seminars and sells starter kits for hobbyists keen to learn how to make their own backyard honey. Kalisz also outfits major apiaries with the equipment and supplies they need to run at commercial scale. He raises his own bee colonies for pollination and honey. And through his firm’s Bee Works gift shop he sells his own and other beekeepers’ honey, along with candles and related products.

This year one of Kalisz’s clients lost all their bees when beavers dammed a nearby creek and flooded the hives. ‘I’d never heard that one before,’ he says bemusedly. ‘Killed by beavers. Only in Canada.’

When asked for his reaction to the latest U.S. predictions regarding a potential 70 percent colony loss rate for 2025, Kalisz dutifully expresses worry about the health of all bees: “It definitely concerns us,” he says. But his very next thought is about how this could impact the Canadian market. “If the U.S. has a shortage of honey, they’ll be buying Canadian honey,” he calculates. “Our prices will be going up for sure.” There’s money to be made.

Kalisz readily admits there is plenty to fret about when raising bees. “There are new pests appearing all the time,” he says in an interview. Beyond mites and viruses, a difficult winter can be deadly for bees. But so can a warm fall. During a warm fall, he explains, wasps and hornets continue to forage, and in the absence of other prey they’ll invade hives to feast on bees and their supplies. And in a surprising new twist, this year one of Kalisz’s clients discovered he’d lost all his bees when beavers dammed a nearby creek and flooded his hives. “I’d never heard that one before,” Kalisz says bemusedly. “Killed by beavers. Only in Canada.”

Making honey, and money: Todd Kalisz, CEO of Port Hope, Ontario-based Dancing Bee Equipment, acknowledges the many risks associated with raising bees. But he remains fiercely optimistic about the industry because of its importance – and the large profits to be made. (Source of photo: Cecilia Nasmith, retrieved from Farmtario)

Making honey, and money: Todd Kalisz, CEO of Port Hope, Ontario-based Dancing Bee Equipment, acknowledges the many risks associated with raising bees. But he remains fiercely optimistic about the industry because of its importance – and the large profits to be made. (Source of photo: Cecilia Nasmith, retrieved from Farmtario)Despite a long and ever-expanding list of threats, however, Kalisz is relentlessly upbeat about the bee business. And the numbers generally back his enthusiasm. Last year Canada produced 78 million pounds of honey worth $214 million. While that value is down somewhat from the record $283 million in 2023, the overall trend is on the rise; like any commodity, honey is subject to the vagaries of supply and demand.

A more reliable source of income lies not in selling the bees’ honey, but in selling their services. Among the major beekeepers on Kalisz’ client list, he says “their primary source of income is pollinator contracts.” One-third of all field crops in Canada, worth over $7 billion annually, require annual pollination by insects. And the only reliable, commercial way to meet this need is with honey bees trucked to the site and allowed to work their magic for the required number of days. Servicing other farmers provides professional beekeepers with a stable, contract-based business model that can be combined with the up-and-down honey market.

Wild Rose Nectar

Within Canada, Alberta bestrides the bee economy like a colossus, leading in both honey production and pollination services. While the province accounts for just 12 percent of Canada’s beekeepers, it has nearly 40 percent of the nation’s bee colonies and an even greater share of honey production. “We love punching above our weight,” says Connie Phillips, executive director of the Alberta Beekeepers Commission. While backyard hobbyists generally represent the lion’s share of other provinces’ beekeeping statistics, the vast bulk of Alberta’s 315,000 colonies are run by a handful of large-scale operators, some with as many as 17,000 colonies each. As Phillips explains, this group tends to be younger than most traditional farmers, and is always eager to experiment and take on new challenges.

A major factor in the Alberta bee industry’s success lies in the province’s key role in hybrid canola seed production. The complex process necessary to create these hybrid seeds requires as many as 70,000 honey bee colonies per year. According to Statcan calculations, honey-bee pollination makes possible a staggering $6 billion worth of canola sales. (Other bee types, such as the leafcutter bee, are also involved in creating the hybrid seeds.)

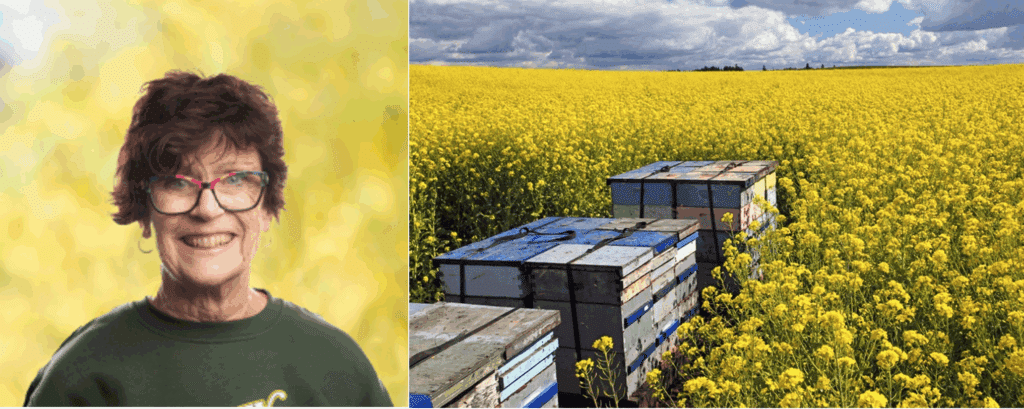

Punching above its weight: Alberta has just 12 percent of Canada’s beekeepers but boasts nearly 40 percent of the country’s honey bee colonies. According to Connie Phillips, executive director of the Alberta Beekeepers Commission, the province’s key role in producing hybrid canola seeds largely explains this dominance. (Sources of photos: (left) Alberta Beekeepers Commission; (right) Ian Sane, licensed under CC BY 2.0)

Punching above its weight: Alberta has just 12 percent of Canada’s beekeepers but boasts nearly 40 percent of the country’s honey bee colonies. According to Connie Phillips, executive director of the Alberta Beekeepers Commission, the province’s key role in producing hybrid canola seeds largely explains this dominance. (Sources of photos: (left) Alberta Beekeepers Commission; (right) Ian Sane, licensed under CC BY 2.0)The Prairies’ ample supply of arable land available for bees to forage – including broad tracts of cattle-grazing fields that are home to numerous flowering plants, including the emblematic wild rose – is another factor in Alberta’s outsized role; Manitoba also has a disproportionately large beekeeping sector for this reason, but tends to specialize in honey exports over pollination services.

About half of Ontario’s 111,000 colonies are also engaged in commercial pollination. Kalisz says a beekeeper can earn $100 per colony for a week or two spent pollinating fruit orchards in the province’s Niagara Peninsula. Once that work is done, it’s off to the blueberry fields of Quebec and the Maritimes, where the same colony can make another $250 to $300. That same rate applies to canola pollination in Alberta. Given the size of some operations, pollinator contracts ranging in the millions of dollars are not uncommon.

And best of all, the bees work for free. “If your bees are healthy and you get a good pollination season out East and then come back home and have good conditions for making honey, then beekeeping can be profitable, very profitable,” Kalisz observes, providing a sharp counterpoint to the constant complaints emanating from others in his industry. “The guys who know how to do that are making lots of money.”

What drives the honey bee industry?

The Bee Economy

Despite many environmental activist groups who regard the bee as a sort of totem upon which the entire plant world depends, honey bees are more accurately regarded as a farm-raised type of livestock, no different in principle from cattle, chickens or salmon. They aren’t even native to North America: honey bees were first imported by European settlers in the 1600s. Ever since their arrival, they’ve been cultivated with deliberate commercial intent – allowing them to outcompete native pollinators such as bumble bees and butterflies even though they remain poorly suited to Canada’s winter. (This highlights the irony of all those native-plant pollinator gardens virtuously installed in neighbourhoods across Canada that end up supporting what is, technically at least, an invasive honey bee population.)

Today, the continued importation of bees remains crucial to the entire industry’s success. When a beehive collapses for whatever reason, the affected commercial beekeeper is motivated to regenerate that colony as swiftly as possible. And while every hive has the ability to create its own queens when necessary, this can be a slow process in the cold Canadian climate. A better option is often to buy a new queen from a warmer country, possibly in the southern hemisphere where the reproduction cycle is different from that in Canada.

Strangers in a strange land: Despite their long presence in North America, honey bees are not native to the continent. They were first imported by European settlers in the 1600s, and today still struggle to adapt to the harsh Canadian climate. Shown, The Beekeepers, a pen and ink drawing by Dutch artist Pieter Bruegel from 1568 showing European apiarists at work. (Source of image: Live Beekeeping)

Strangers in a strange land: Despite their long presence in North America, honey bees are not native to the continent. They were first imported by European settlers in the 1600s, and today still struggle to adapt to the harsh Canadian climate. Shown, The Beekeepers, a pen and ink drawing by Dutch artist Pieter Bruegel from 1568 showing European apiarists at work. (Source of image: Live Beekeeping)Kalisz imports 50,000-70,000 queens every spring from countries pre-approved by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, which include the U.S., Australia, New Zealand, Italy and Chile. Depending on their provenance, most queens retail for $35 or $50 each. And in what can only be described as a miracle of nature, each queen can lay up to 2,500 eggs per day, with the size of the egg chamber and the orientation of the egg determining whether each egg hatches to become a drone (male), worker (female) or even a new queen if required. It only takes a few weeks to go from egg to larva to maturity. “Bees are incredible at reproducing,” Kalisz gushes. “You can make bees very quickly.”

While a 70 percent loss rate would slow even a determined beekeeper’s bounce back, vigorous international trade in bees keeps the risk of a permanent bee apocalypse firmly at bay. In 2024, Canada imported 300,000 queens worth $12 million, alongside another $6.5 million worth of bee packages.

The amazing reproductive abilities of bees means even an apparently devastating winter loss can quickly be recouped by a motivated and prepared beekeeper. “Say you find out in March that 50 percent of your bees are dead, but you still have pollination contracts you have to fulfill in May,” Kalisz explains. “A commercial beekeeper will then order new queens from Chile to arrive in April.” Halving the remaining healthy hives and inserting new imported queens into those split colonies allows a beekeeper to quickly refresh their bee capital and get back to production levels in time to fulfil any contractual obligations. It is also possible to import “bee packages” that include a queen and 8,000 to 10,000 mature bees.

“You can make bees very quickly”: A queen bee (centre, marked by green paint) can lay up to 2,500 eggs per day. As Kalisz explains, this makes it possible for a dedicated beekeeper to bounce back from even a devastating 50 percent winter loss rate. (Source of photo: quisnovus, licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0)

“You can make bees very quickly”: A queen bee (centre, marked by green paint) can lay up to 2,500 eggs per day. As Kalisz explains, this makes it possible for a dedicated beekeeper to bounce back from even a devastating 50 percent winter loss rate. (Source of photo: quisnovus, licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0)While Kalisz admits a 70 percent loss rate would slow even a determined beekeeper’s bounce back, vigorous international trade in bees keeps the threat of a permanent bee apocalypse firmly at bay. In 2024, Canada imported 300,000 queens worth $12 million, alongside another $6.5 million of bee packages. While the U.S. is the top source of queen bees, lingering concerns about America’s old killer bee problem means the federal government only allows bee packages to come from New Zealand, Italy, Australia or Chile. Adds Phillips, “Imports have been sustaining our industry for 20 years” – in other words, since before the onset of CCD.

The Real Risks

If there is a real threat to the survival of Canada’s bee population, it is not health-related. It lies in man-made policy errors. Any permanent disruption in the cross-border bee trade via tariffs or other similar mistakes would present an acute and immediate danger to the entire industry. With this in mind, and given the centuries-old struggle to get imported honey bees to fully adapt to Canada’s forbidding climate, efforts are underway to breed a hardier Canadian variant.

Kalisz sells his own version called the North Star for $65 each. There are similar efforts ongoing across the country, including a $4.5 million federally-funded project involving researchers in several provinces. In Alberta, Phillips explains that “a lot of our producers are starting to raise their own queens to reduce their dependency on imports.” Developing a new domestic queen not only offers large commercial beekeepers an insurance policy on future trade risks, but opens another potential revenue stream as well.

Precious international cargo: In 2024, Canadian beekeepers imported 300,000 queen bees from other countries, including the U.S., Australia, New Zealand, Chile and Italy. Shown at bottom, wooden queen boxes each containing a queen, her attendant bees and their food supply upon arrival. (Source of photos: Charlotte Ekker Wiggins, retrieved from Home Sweet Bees)

Precious international cargo: In 2024, Canadian beekeepers imported 300,000 queen bees from other countries, including the U.S., Australia, New Zealand, Chile and Italy. Shown at bottom, wooden queen boxes each containing a queen, her attendant bees and their food supply upon arrival. (Source of photos: Charlotte Ekker Wiggins, retrieved from Home Sweet Bees)Unfortunately for Canadian taxpayers, they are also getting dragged into the phony Bee Apocalypse scare. While beekeeping represents only a tiny slice of Canada’s $31 billion per year primary agriculture sector, the industry seems increasingly interested in following its bigger cousins into leveraging doomsday headlines for financial gain. Following a 45 percent winter die-off in 2022, for example, many beekeeping associations wrangled compensation packages from their provincial and federal governments. In Alberta this took the form of the Canada-Alberta Bee Colony Replacement Assistance Initiative, which paid out $210 per lost colony and $35 per dead queen for any losses over 30 percent.

A similar program in Saskatchewan “invested” $1 million by covering 70 percent of the cost of replacement colonies. Yet Phillips still grumbles that government programs for beekeepers pale next to the funding provided to the other agricultural categories, especially for dairy cattle. “That kind of support just isn’t there for bees,” she says. Given the stranglehold Canada’s inefficient and insular dairy sector has over Parliament, taxpayers and consumers should hope not.

Other broad-based bee risks include ongoing campaigns by environmental groups demanding Canada follow the European lead and ban neonic pesticides entirely. Given the exhaustive federal government research already complete on the topic, such a move would have little impact on bee health. But it could dramatically reduce crop productivity and thereby make food even more expensive. It could also push farmers to use other, less-well-studied pesticides that pose greater threats to beneficial insects.

The statistical truth is that things have rarely been better for bees around the world. Yes, bees die, sometimes in very large numbers. But – and this is the bit the headlines always omit – they come back. Because the market needs them to come back.

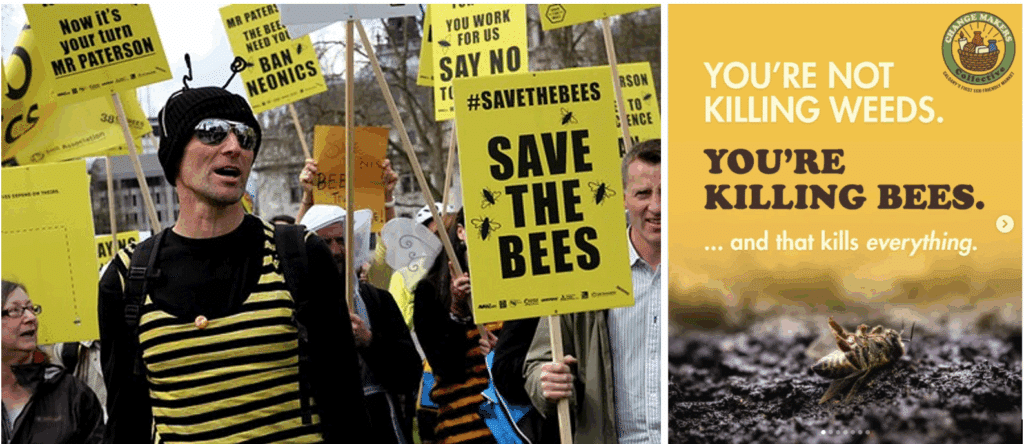

Additionally, homeowners might notice the many finger-wagging admonitions on social media that they should personally be doing more to save bees. One example among many is a series of Instagram posts by the Calgary-based Change Makers Collective that yells in all-caps “YOU’RE NOT KILLING WEEDS. YOU’RE KILLING BEES” – and tries to browbeat homeowners into not mowing or spraying their lawns, ostensibly to help keep bees fed on dandelions in the spring. While Kalisz says he never mows or sprays his lawn as a matter of principle, commercial beekeepers often feed their bees sugar syrup when there’s no forage nearby. Leaving one’s lawn fallow mainly serves to make one’s neighbourhood uglier. Besides, most bees don’t live in the suburbs.

The “other” bee risks: Environmentalist campaigns to save bees can do more harm than good. At left, a 2013 demonstration against neonicotinoid pesticides in London, England; at right, a 2025 Instagram post by the Calgary-based Change Makers Collective admonishing local homeowners to leave their lawns unkempt. (Source of left photo: Sputnik UK, licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0)

The “other” bee risks: Environmentalist campaigns to save bees can do more harm than good. At left, a 2013 demonstration against neonicotinoid pesticides in London, England; at right, a 2025 Instagram post by the Calgary-based Change Makers Collective admonishing local homeowners to leave their lawns unkempt. (Source of left photo: Sputnik UK, licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0)Bees 4 Ever

Given the repetitive and incessant buzz about bees disappearing, the single most important fact to remember is that there’s no shortage of them in Canada or anywhere else in the world. Earlier this year, Germany’s official statistical agency reported that the worldwide beehive count rose from 69 million in 1990 to 102 million in 2023, with Europe and Africa showing the biggest growth. Globally, China is now the world’s top honey exporter, accounting for over 12.5 percent of international trade in the sticky stuff, with tiny New Zealand in second at 11.9 percent. (Canada is 17th with a slim 1.7 percent share.)

Another study in the academic publication Scientific Reports in 2022 found the number of honey-bee colonies worldwide “nearly doubled” between 1961 and 2017, while honey production “almost tripled” and beeswax production doubled. As this report by New Zealand and UK researchers observes, hysterical reports about mass bee die-offs are always local in nature. The bigger, longer-term picture shows robust growth around the world, and especially in Asia, Africa and South America. From the report: “Headlines of honey bee colony losses have given an impression of large-scale global decline of the bee population that endangers beekeeping, and that the world is on the verge of mass starvation.” Such claims, the authors deadpan, are “somewhat inaccurate.”

The statistical truth is that things have rarely been better for bees around the world. Yes, bees die, sometimes in very large numbers. But – and this is the bit the headlines always omit – they come back. Because the market needs them to come back. And the market always finds a way. “This industry is never going to disappear,” says master beekeeper Kalisz assuredly. “We need the honey and we need the pollination.”

Keeping busy: According to a 2022 study in the journal Scientific Reports, the global bee population has “nearly doubled” since the 1960s and honey production has “almost tripled,” with much of that growth occurring in South America, Asia and Africa. Barring any massive trade policy errors, there’s no need to fear bees will ever disappear. Shown, spectacular cliffside honey-bee colonies in Mount Qingcheng, Sichuan, China. (Source of photo: Shutterstock)

Keeping busy: According to a 2022 study in the journal Scientific Reports, the global bee population has “nearly doubled” since the 1960s and honey production has “almost tripled,” with much of that growth occurring in South America, Asia and Africa. Barring any massive trade policy errors, there’s no need to fear bees will ever disappear. Shown, spectacular cliffside honey-bee colonies in Mount Qingcheng, Sichuan, China. (Source of photo: Shutterstock)

대화 참여하기