Attributing climate and weather extremes to Northern Hemisphere sea ice and terrestrial snow: progress, challenges and ways forward

Attributing climate and weather extremes to Northern Hemisphere sea ice and terrestrial snow: progress, challenges and ways forward

Abstract

Sea ice and snow are crucial components of the cryosphere and the climate system. Both sea ice and spring snow in the Northern Hemisphere (NH) have been decreasing at an alarming rate in a changing climate. Changes in NH sea ice and snow have been linked with a variety of climate and weather extremes including cold spells, heatwaves, droughts and wildfires. Understanding of these linkages will benefit the predictions of climate and weather extremes. However, existing work on this has been largely fragmented and is subject to large uncertainties in physical pathways and methodologies. This has prevented further substantial progress in attributing climate and weather extremes to sea ice and snow change, and will potentially risk the loss of a critical window for effective climate change mitigation. In this review, we synthesize the current progress in attributing climate and weather extremes to sea ice and snow change by evaluating the observed linkages, their physical pathways and uncertainties in these pathways, and suggesting ways forward for future research efforts. By adopting the same framework for both sea ice and snow, we highlight their combined influence and the cryospheric feedback to the climate system. We suggest that future research will benefit from improving observational networks, addressing the causality and complexity of the linkages using multiple lines of evidence, adopting large-ensemble approaches and artificial intelligence, achieving synergy between different methodologies/disciplines, widening the context, and coordinated international collaboration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sea ice and seasonal snow (hereafter snow) are two indispensable components of the cryosphere that play an important role in climate variations and change. Their variations modulate surface energy balance and trigger atmospheric circulation response1,2,3. Both Arctic sea ice and spring snow cover in the Northern Hemisphere (NH) have been rapidly decreasing in recent decades amid global climate change4,5,6. Arctic sea ice loss has been considered as a key driver of the Arctic amplification of global warming (AA)7,8, amid rapid climate change in the Arctic climate system9. Studies have linked changes in sea ice and snow cover with climate and weather extremes manifesting as, for example, heatwaves10, droughts11 and cold spells12, which have caused substantial socioeconomic damages. Understanding the link between sea ice and snow change, and extreme events can potentially enhance predictions and projections of these extremes, contributing to climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Over the past several decades, many studies have attempted to attribute these climate and weather extremes to sea ice and snow change, but the idea remains contentious, and studies are somewhat polarized and fragmented. Drivers of extreme events are multifaceted and attribution of extreme events is challenging13,14. Isolating the effects of sea ice and snow change from other competing factors such as internal atmospheric variability and sea surface temperature (SST) may be more complicated than previously perceived. Projected Arctic sea ice loss is not found to significantly drive climate variability and atmospheric circulation change in recent comprehensive climate modeling15,16. While autumn snow cover anomalies have been proposed to induce winter extreme weather in the NH12,17, their role as a driver of such extremes remains controversial. On the other hand, snow loss, in the form of unusually low snow water equivalent (SWE) usually termed snow droughts18, has been increasingly linked with spring-summer extreme events19. These have raised questions about whether sea ice or snow change is still a potentially important driver of extreme events and what will be needed to facilitate further significant advances in this area of research.

Climate projections suggest that future extreme events such as heatwaves and extreme precipitation will increase and intensify and that they will tend to break previous records by much larger margins, while Arctic sea ice and snow will continue to decrease according to the Sixth Assessment Report of the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC AR6)20,21. In particular, the earliest Arctic ice-free conditions for September are likely going to occur by 2050 irrespective of emission scenarios22. Further, Arctic sea ice extent (SIE) minimum has a downward trend of 12.4 percent per decade from 1979 to 2024 relative to the 1981 to 2010 average with the year of 2012 setting the record minimum (https://nsidc.org/sea-ice-today/analyses/arctic-sea-ice-extent-levels-2024-minimum-set). Spring snow cover extent (SCE) over the NH is projected to decrease by about 8% relative to the 1995–2014 level per degree Celsius of global surface air temperature (GSAT) increase6. Both the years 202323 and 2024 successively broke the temperature records with the latter at about 1.55 °C above pre-industrial level according to the World Meteorological Organization (https://wmo.int/news/media-centre/wmo-confirms-2024-warmest-year-record-about-155degc-above-pre-industrial-level). These suggest global climate change may evolve beyond our current understanding and projections. There is a window of opportunity to accelerate progress in attributing climate and weather extremes to sea ice and snow change so that critical information can be used to assist the predictions of these extremes and to mitigate the societal and ecological damages linked with a changing cryosphere. Therefore, there is an urgent need to review our current progress in attributing climate and weather extremes to sea ice and snow change and to suggest a way forward in this area of research.

Previous review papers have focused on the impacts of sea ice or snow on climate and weather variability2,24,25. In this review, we synthesize the major progress in attributing climate and weather extremes to sea ice and snow change in the NH in terms of observed linkages, physical pathways and uncertainties. While sea ice and snow are often considered separately in many studies for attributing extreme events, there has been an increasing trend to consider their combined influences26,27,28. We consider both sea ice and snow in this review, both of which are highly sensitive and vulnerable to global warming and climate change, to highlight some of their shared mechanisms and their combined influences on extreme events. This approach emphasises the benefits of considering the influence of both sea ice and snow changes on extreme events under the same framework and highlights the cryospheric feedback to the climate system. Built on the recent advances and emerging opportunities, we suggest ways forward to make further advances in this area of research. This review will thus serve as a bridge between current progress and future advances in attributing climate and weather extremes to sea ice and snow change.

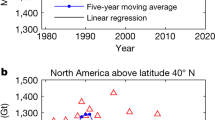

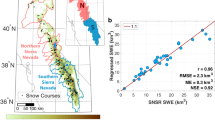

Observed linkages between a changing cryosphere and extremes

Both SIE and sea ice concentration (SIC) in the Arctic have been decreasing during the satellite era (Fig. 1a, f), consistent with the global warming trend in GSAT. The Arctic has also lost more than 2 × 106 km2 of multiyear sea ice over the scatterometer record (1999–2017) (Kwok, 2018). An ice-free Arctic, defined as having less than 1 million square kilometers of September sea ice area, is projected to occur by 2050 independent of emission scenarios22. There are also concurrent downward trends in NH spring SCE (solid lines, Fig. 1b), and in winter snow water equivalent (SWE)29 in North America and west Eurasia (Fig. 1f). Both the summer sea ice decline and spring SCE decline are considered to be of very high confidence according to IPCC AR620. The autumn SCE in the NH shows contrastingly significant upward trends (blue and red dashed lines, Fig. 1b), though the recent decades of Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer data30 show weakly insignificant downward trends (yellow dashed line). Trends in the NH autumn snow cover are less monotonic and projections of them are less confident than those for spring31. For the lowest five NH SCE values for each month in the period of March–June, seventeen out of twenty values occurred after 1990 between 1967 and 201532. Snow drought durations over eastern Russia, Europe, and western United States have lengthened by ∼2, 16, and 28%, respectively, in the latter half of 1980 to 201818. Causes of the changes in Arctic sea ice are found to be related to the Arctic dipole33, Arctic cyclones34, sea ice thinning35 or a combination of different factors36. An extreme SIE minimum of the magnitude seen in 2012 is not likely to occur without anthropogenic influence37. Cold season Arctic cyclone number has a strong positive trend from around 2000 with a causal connection to both the warm and cold season Arctic sea ice loss, which suggest that cyclones caused changes in the sea ice38. August cyclones have become more destructive in accelerating Arctic sea ice loss during 2009–18 compared to 1991–200039. Moreover, Arctic minimum SIE is jointly influenced by the strength of the cyclone, its timing and its location relative to the sea ice edge40. In addition, multidecadal variability in Arctic sea ice has been reported41,42,43,44,45, though it is less clear for snow. The extent to which recent trends in Arctic sea ice and snow are influenced by multidecadal variability remains to be clarified.

대화 참여하기